Congrats to George Porter, Jr....

[On the Button]...for his 2012 Lifetime Achievement Award from OffBeat magazine, celebrated by George and his band at the Best of the Beat Awards show last night, where quite a party broke out. Read Alex Rawls' great interview with the bassist wtih the funky mostest, which also appeared in the January print issue with George gracing the cover.

[On the Button]...for his 2012 Lifetime Achievement Award from OffBeat magazine, celebrated by George and his band at the Best of the Beat Awards show last night, where quite a party broke out. Read Alex Rawls' great interview with the bassist wtih the funky mostest, which also appeared in the January print issue with George gracing the cover.

He got well-deserved kudos and gave a very gracious thank-you to his wife of 40+ years, who he brought out onstage and handed the award, saying he was giving it to her for all her support, then delivered an outstanding, feel-good performance with the Runnin' Pardners. Plus, dig who dropped by for the warm-up musical tribute put together by his daughter, Katrina: Art Neville, Cyril Neville, Dr. John, David Barard, Papa Mali, Stanton Moore, and George's horn section alumni. Not too shabby.

As the pulse of so much vital New Orleans music, how could George ever NOT matter?  [George and Terrence Houston, well into it (photo by Dan Phillips)][P.S. - George's segment wasn't the only music, by far, with two stages going pretty much all night. See the line-up at the BOTB link above.]

[George and Terrence Houston, well into it (photo by Dan Phillips)][P.S. - George's segment wasn't the only music, by far, with two stages going pretty much all night. See the line-up at the BOTB link above.]

Utterly Etta

I thought I’d consider a few tunes from the HOTG perspective in remembrance of Etta James, one of soul music’s most expressive singers, who passed away last Friday at 73. She was preceded just a few days earlier by the great Johnny Otis, who had discovered her in San Francisco in 1954 and brought her down to Los Angeles to record for Modern Records, the first session resulting in a hit, “The Wallflower”. Though not a New Orleans artist by any means; Etta did record there a couple of times, starting in 1956-57, when Modern brought her in to cut some sides at Cosimo Matassa’s original Rampart Street studio, J&M, ground zero for a multitude of classic records that decade, many hits, many misses. Two good singles resulted,, “Tough Lover”/”What Fools We Mortals Be” (#998) and “The Pick-Up”/” Market Place” (#1016), with Etta backed by members of the hot pool of local players who gave tracks cut as Cosimo’s their distinctive energy and sound; but nothing from those sessions fared well commercially - so she moved on...and on. By the time she returned to the city for an album project nearly a quarter century later, she was an acknowledged soul diva, albeit one who was having mid-life label problems. Much in the music business had changed. Yet, New Orleans still proved to be a great place to make a record..

Though not a New Orleans artist by any means; Etta did record there a couple of times, starting in 1956-57, when Modern brought her in to cut some sides at Cosimo Matassa’s original Rampart Street studio, J&M, ground zero for a multitude of classic records that decade, many hits, many misses. Two good singles resulted,, “Tough Lover”/”What Fools We Mortals Be” (#998) and “The Pick-Up”/” Market Place” (#1016), with Etta backed by members of the hot pool of local players who gave tracks cut as Cosimo’s their distinctive energy and sound; but nothing from those sessions fared well commercially - so she moved on...and on. By the time she returned to the city for an album project nearly a quarter century later, she was an acknowledged soul diva, albeit one who was having mid-life label problems. Much in the music business had changed. Yet, New Orleans still proved to be a great place to make a record..

Over the years, Etta put her distinctive stamp on number of songs by New Orleans and Louisiana writers, including Eddie Bo, Allen Toussaint, King Floyd, Bobby Charles, and David Egan. Almost exactly 5 years ago, I featured this cover of a rarely heard Toussaint tune; which has never been topped. It’s definitely time for a replay. “Blinded By Love” (Allen Toussaint) Etta James, from Etta Is Betta than Evvah, Chess 1976

“Blinded By Love” (Allen Toussaint) Etta James, from Etta Is Betta than Evvah, Chess 1976

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

That prior post considered three of the four known versions of “Blinded By Love”: Sam and Dave’s, produced by Steve Cropper in 1975 with a bunch of cool Stax alumni; Lydia Pense and Cold Blood’s funky bar band stab; and, of course, Etta’s, which I still attest to be the finest by far.

This unique, meticulously crafted Toussaint rock-pop hybrid can trip up the best of players with all its interlocking, tightly turned, precision-demanding riffs. On such material, the danger is losing the groove while negotiating the rapid-fire ins and outs to perfection. Undeterred by the challenge, producer/arranger Mike Terry decided to de-emphasize the riffs in favor of feel via finely tuned poly-rhythmic support that was on the money, in the pocket, but not in the way. That opened up the track and allowed Etta’s funky, expansive soul room to breathe. She certainly had her way with the enigmatic lyrics, making them matter purely by her intonation, phrasing and dynamics. “Groove Me” (King Foyd)

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Speaking of covers, she utterly dominated King Floyd’s “Groove Me” on this same album, her inventive melodicism and raw power taking it places Floyd never dreamed of. Luckily for him, few people ever got to hear her kick his ass. Terry kept the basic song structure intact, including the vital staggered bass line that gives the tune its herk-jerky fever, but employed his larger instrumental palette to create a pulsing cluster of rhythmic interplay that provided uplifting, booty-shifting support for Etta’s high caloric, deep-fried bump and grind vocalizing.

I note that Larry Grogan also tapped this one as part of his fine Etta tribute from the past weekend at Funky 16 Corners; but I’ve wanted to post it for so long, I’m going with it anyway - the more the funkier. For an extra-treat, you can catch her doing the song live in 1982 on YouTube, with Toussaint and Dr. John sitting in, no less

An enjoyable ride, this poorly titled and cheaply packaged LP marked the end of Etta’s association with Chess Records and quickly slipped into undeserved obscurity due to a chain of corporate upheavals. She had first signed with the Chicago company in 1960 and recorded most of her classic sides for the Chess brothers’ various labels. Once they sold out to GRT in 1969, recording activity tapered off over the next few years, and the Chess physical assets were liquidated.

Around 1976, All Platinum Records bought the remains from GRT, mostly for the rich back-catalog of music, but ponied up to make Etta Is Betta Than Evvah, tracking most of it at their New Jersey studios. The result likely was the last new recording ever to bear the Chess imprint, as All Platinum soon found it more lucrative to simply reissue the label archives, as did Sugar Hill when they took over a few years later, followed by MCA, et al, keeping the Chess name alive through perpetual re-packaging.

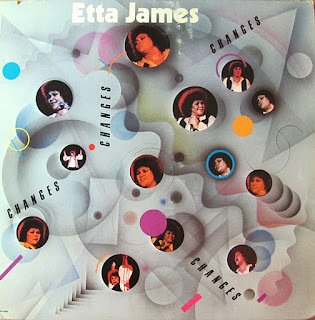

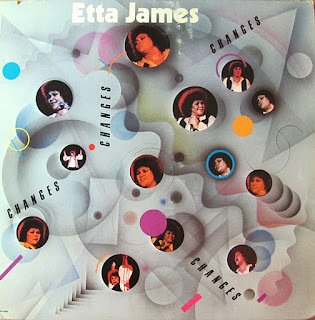

Etta signed with Warner Brothers in 1978 and recorded her fine Deep In The Night album in L.A. with Jerry Wexler producing, but it experienced the age-old music business curse of raves from the critics and indifference from the public. So, WB sent her down to Sea-Saint in New Orleans to work on a follow-up, aptly entitled Changes, with Toussaint in charge. He gave the proceedings variations on his usual mix of soul, pop and funk, with emphasis on the former and latter, considering who was singing, and got a number of impressive performances from Etta. I’ve featured several songs from this great album before, most recently as part of my series on the late Herman Ernest, III, who did a lot of the drumming on it; and the revealing back story of those sessions is there for the reading.

The Changes LP took over a year to complete, because, in the midst of the process, Warner Brothers heard the rough cuts and decided to dump the album and Etta. Go figure. Put on indefinite hold, the project picked up again when RCA showed interest in it, only to have them also back out on the deal. Finally, after many months, MCA stepped in and funded completion the LP, releasing it on their T-Electric imprint; but it seems they then forgot it existed, as the record sank in the commercial shark tank pretty much without making a ripple. “Changes” (Carole King [??]) Etta James, from Changes, T-Electric, 1980

“Changes” (Carole King [??]) Etta James, from Changes, T-Electric, 1980

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

I‘m so fascinated with this unusually structured, deep soul title track, I had to ignore my own preference for the upbeat and include it. Toussaint’s artful arranging and production ingenuity were well-expressed here in the slow, swing/sway of the beat, set in a floating 6/8 time with certain rythmic liberties taken at points for contrast and added kick. The studio band rendered it all flawlessly; and the leader's churchy piano vamping set the tone and provided the platform for the authentic, soulful authority of Etta’s delivery. That she was the realest of deals is undeniable on this tune, where her always mind-blowing vocal power is under such effortless control and perfectly attuned to the track.

There’s one mysterious caveat to this number. Regardless of what the back cover and label credits say, it appears not to have been written by Carole King at all. Neither the lyrics nor the melody match the song of the same name on King's 1978 Welcome Home album - the only song with that title she wrote, by the way. I have been unable to find a correct or even plausible attribution* for Etta's “Changes”, but feel there must have been a mix-up in the performing rights/song licensing department at the company, and would appreciate any leads you can lend as to who the writer(s) might be.

For a nice summary of Etta’s career, be sure to hop over to The B-Side and read what Red has to say about this all too human, yet larger than life singer’s singer, whose voice that had no compare or competition, belonging in a timeless class unto itself. Utterly irreplaceable.

*Note: Toussaint’s BMI catalog of songs includes one with the same title, and shows three co-wrtiers, who turn out to have written it in the 1990s, when it appeared on the Clockers soundtrack. Including Toussaint on the credits is either a BMI mistake, or may have something to do with the subtitle of that song being “Get Out of My Life Woman”. The US Copyright Ofiice does not show “Changes” as a registered Toussaint composition.

The New(er) Dark Ages?

Since today is Black Wednesday, I thought I'd act like a real blog today and just post a link to this piece on Mashable which says better than I could what all this SOPA/PIPA obfuscating is really about....and it ain't online piracy, folks.

Not that I support pirating; but nuking the internet, or attempting to make it serve just a few masters, is no solution. In the immortal words of the Isley Brothers...and Public Enemy..."Fight the Power!"

Steppin' Into Carnival 2012

Well, I just looked up for a minute from the near constant keyboard tapping, information seeking, and record cleaning/listening rituals around here to find the new year fully engaged and Twelfth Night already past. Damn, tempus fugeddaboutit. It’s time to stand back up and start celebrating all over again, and not just because the Saints continue their winning Who Dat ways....

Well, I just looked up for a minute from the near constant keyboard tapping, information seeking, and record cleaning/listening rituals around here to find the new year fully engaged and Twelfth Night already past. Damn, tempus fugeddaboutit. It’s time to stand back up and start celebrating all over again, and not just because the Saints continue their winning Who Dat ways....

It's Carnival season, y'all, in no way to be confused with the current Circus of the Absurd masquerading as presidnetial campaigning, traveling state to state to peddle assorted vaporous remedies purported to cure all ills. What better time for a far more efficacious remedy, two quick shots of street-occupyin' funk to help get the juices flowing for all the partying, parading, and other polymorphously festive proclivities to come, as anticipation builds for Mardi Gras, February 21st, 2012. Eh las bas!

On deck we have some early Rebirth Brass Band action transferred from rare vinyl, plus an LP cut from the Wild Tchoupitoulas Mardi Gas Indians, featuring the late Big Chief Jolly. Let’s go get ‘em!

“Put Your Right Foot Forward” (Kermit/Philip)Rebirth Brass Band, Syla 986, ca 1987

“Put Your Right Foot Forward” (Kermit/Philip)Rebirth Brass Band, Syla 986, ca 1987

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

This single on Milton Batiste’s Syla label likely came out around Mardi Gras in the late ‘80s, no doubt as a fairly limited edition, since Syla releases got spotty distribution at best, even around their city of origin. My bunged up copy - the only one I’ve run across, so far - turns out to be an interesting artifact in the Rebirth’s coming of age saga.

The group formed in the early 1980s, when three teenage high school friends and marching bandmates, trumpeter Kermit Ruffins and the Frazier brothers, tubist Philip and bass drummer Keith, started a brass and percussion unit, Rebirth Jazz Band. The group was inspired by the revolutionary Dirty Dozen, who were already busy around town making a splash and the resulting waves by updating traditional street parade sound with slamming new material, both originals and adventurous cover tunes. The Dozen, Rebirth and a host of other new groups who would follow revived the dying brass band genre, injecting it with the fresh, improvisatory energy, and unstoppably funky grooves that define it to this day.

Rebirth honed their chops playing for tips on the street in the French Quarter and around their home base, the historic Treme neighborhood. With a well-chosen name that was a straightforward statement of their intent, they have kept the innovative intensity going for 30 years. In the early 1990s, Kermit left them to pursue a successful solo career; but neither that nor the Federal Flood stopped the band, whose latest in a long string of albums, Rebirth of New Orleans, is up for a Grammy this year.

Rebirth honed their chops playing for tips on the street in the French Quarter and around their home base, the historic Treme neighborhood. With a well-chosen name that was a straightforward statement of their intent, they have kept the innovative intensity going for 30 years. In the early 1990s, Kermit left them to pursue a successful solo career; but neither that nor the Federal Flood stopped the band, whose latest in a long string of albums, Rebirth of New Orleans, is up for a Grammy this year.

In 1984, the group’s first LP, Here To Stay (re-issued on CD in 1997), was recorded live by roots music propagator Chris Strachwitz at the Grease Lounge in the Treme, and released on his Arhoolie label. By the time they made their next LP/CD, Feel Like Funkin’ It Up, for Rounder Records in 1989, they were going by Rebirth Brass Band exclusively. The Boston-area label was bigger and had much wider distribution than Arhoolie, plus two fine producers, Scott Billington and Ron Levy, focused on bringing numerous New Orleans artists, old and new, to national prominence with well-produced showcase releases.

I’m thinking Rebirth cut this single somewhere in-between those two albums. Although they were shown as Rebirth Brass Band on the label, Kermit’s spoken intro to “Put Your Right Foot Forward” says it’s “...a new one by the Rebirth Jazz Band....” - either a slip, or the name was still in flux. Batiste had taken them into Sea-Saint Studio in 1987 to record a number of sides, four of which appeared two years later on a Rounder brass band compilation, Down Yonder. There the band was billed as the Rebirth Marching Jazz Band, an awkward variant that thankfully did not stick. Anyway, the tracks on this single (with “The New Second Line” on the flip) may well have been cut at the same session.

At Sea-Saint, the band was again recorded live, pumped up to ten pieces from its typical eight in those days, but the the core as listed on the notes to the CD were lead vocalist Ruffins and Derek Wiley on trumpets, the Frazier’s holding down the bottom, Eric Sellers on snare, plus tenor saxophonist John Gilbert, with Keith ‘Wolf’ Anderson and Reginald Stewart on trombones. As the track attests, by this point they were already well-seasoned and smokin’.

“Indians Here Dey Come” (George Landry)from Wild Tchoupitoulas, Antilles, 1976

“Indians Here Dey Come” (George Landry)from Wild Tchoupitoulas, Antilles, 1976

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Of course, Mardi Gras Indians are another phenomenon of the by-ways of the city’s black neighborhoods, traditionally appearing in their colorful regalia on Mardi Gras, and again around St, Joseph’s Day. With their increasing popularity, some also suit up at other times of the year for special events and paying gigs, such as JazzFest. Their long, intriguing history, with cultural roots going back to pre-colonial Africa, is well worth exploring.

George Landry, who wrote and sang this tune, was the uncle of the brothers Neville: Aaron, Art, Charles, and Cyril. He is best known as Big Chief Jolly, leader of the Indian gang, the Wild Tchoupitoulas. that he founded during the early 1970s on the family’s Uptown 13th Ward home turf.

In 1970, another group of Uptown Indians, the Wild Magnolias, under Big Chief Bo Dollis, had a historic jam session with Willie Tee and his funk group, the Gaturs, which resulted in the two groups having a succession of fecund collaborations on recordings over the next few years, including several local singles, and two LPs in 1974 and 1975. Their popularity added yet another facet to the inter-related marvel that is New Orleans music and brought the Indians to the eyes and ears of the world. Naturally, coming from a highly musical family, Jolly and his nephews sought to make their own recorded statement based upon his take on the Indians’ songs and the many cultural influences within them.

The resulting Wild Tchoupitoulas album, was recorded at Sea-Saint and released in 1976 on the Island Records subsidiary, Antilles, and had a couple of 45 spin-offs. Although Sea-Saint owners Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn of Sansu Enterprises got the production credit on the LP for working the deal, they at least allowed Art and Charles to have co-producer and arrangement props; but, as Art pointed out in the brothers’ autobiography, he, Jolly, and all the musicians involved had a part in the production process and contributed more than just their fine chops to the overall sound.

The resulting Wild Tchoupitoulas album, was recorded at Sea-Saint and released in 1976 on the Island Records subsidiary, Antilles, and had a couple of 45 spin-offs. Although Sea-Saint owners Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn of Sansu Enterprises got the production credit on the LP for working the deal, they at least allowed Art and Charles to have co-producer and arrangement props; but, as Art pointed out in the brothers’ autobiography, he, Jolly, and all the musicians involved had a part in the production process and contributed more than just their fine chops to the overall sound.

Art and Cyril were part of the legendary Meters, under contract with Sansu at this point; and the group became the rhythm section for the project, with added percussion by members of Jolly’s gang. Aaron, whose career was at loose ends, contributed his unmistakable vocal skills; and Charles, who was living in New York, was summoned down to play saxophone. It was the first time that all four brothers had recorded together and set the spark that encouraged them to unite as the Neville Brothers band for an epic, multi-decade ride, once Art and Cyril left the Meters in 1977.

Obviously, a lot of incredible talent and good energy was devoted to this LP, which proved to be a charmingly melodic experience with a pronounced Caribbean feel at times, riding relaxed but highly poly-rhythmic grooves. Though well-received by New Orleans aficionados and the music press, it never was a big seller. Sansu claimed it barely made enough money to recoup the production costs; and, thus, little or no royalties were paid out, souring Jolly on doing any more recording. Still, over the years, Wild Tchoupitoulas has become a Carnival music classic and a must-have for any decent collection of the city’s feel-good music.

I'll be back closer to the day with more Carnival tunes. Party on.....

TRACKING THE BIG Q FACTOR, PT 3: More on the Malaco School Bus Sessions & Beyond

Happy New Year, y’all.

Rob Bowman’s extensive notes to the 1999 box set, Malaco Records: The Last Soul Company, revealed a lot to me when it first came out about Wardell Quezergue’s years working out of the company’s Jackson, MS studio, including the exact line-up of vocalists he and his partner, Elijah Walker, brought up from New Orleans on May 17, 1970 to wrap up their first big production project there. That trustworthy account, backed up by Knight’s recollections to Jeff Hannusch in The Soul of New Orleans, have Knight, King Floyd, Bonnie & Sheila, the Barons, and Joe Wilson all tracking vocals on songs which were eventually released on singles by various labels.

Since I covered the Barons’ Malaco sessions in the prior post (just scroll down, if you missed it), this installment focuses on the rest of the slate and examples of records they made at the studio under Big Q’s direction. Most of the contingent took that first trip up in a funky, old, un-air-conditioned school bus that Walker arranged for, an appropriate conveyance in a sense, when you consider the way Wardell schooled singers and musicians for his sessions, and the poly-rhythmic grooves to be found on many of the resulting tracks.

What he presided over during his tenure at Malaco was actually a unique re-allignment of the funk feel, first expressed by his arrangement of King Floyd’s “Groove Me”. Since the song is fairly well-known and easily accessible, I’m not featuring the audio here; but how it came to be, got the Big Q treatment, and became a hit is essential to the story. So find a copy and listen up if you like, as we move along.

Groovin’ With the King

When Floyd composed “Groove Me” a year or two prior to cutting it at Malaco, he was in California working with Harold Battiste, Mac Rebennack, and other New Orleans expatriates on recording and songwriting. He had the song pegged to be funky from the start with the offbeat bass line as its centerpiece; but the tune would have to wait for Wardell to realize its full potential. Floyd almost allowed another artist to record it out West, but balked then the producer of the project wanted to straighten out the groove. Upon returning home, he pitched it to several other vocalists, one of whom, C. P. Love, just happened to be managed by Walker and slated to be a part of the May 17 Malaco sessions. So impressed was Love with Floyd and his songs, “Groove Me” in particular, he offered to let him have his recording slot; and, once Big Q heard Floyd’s material, he readily agreed to the switch. So, the new recruit signed on and was prepped for his performance.

When Floyd composed “Groove Me” a year or two prior to cutting it at Malaco, he was in California working with Harold Battiste, Mac Rebennack, and other New Orleans expatriates on recording and songwriting. He had the song pegged to be funky from the start with the offbeat bass line as its centerpiece; but the tune would have to wait for Wardell to realize its full potential. Floyd almost allowed another artist to record it out West, but balked then the producer of the project wanted to straighten out the groove. Upon returning home, he pitched it to several other vocalists, one of whom, C. P. Love, just happened to be managed by Walker and slated to be a part of the May 17 Malaco sessions. So impressed was Love with Floyd and his songs, “Groove Me” in particular, he offered to let him have his recording slot; and, once Big Q heard Floyd’s material, he readily agreed to the switch. So, the new recruit signed on and was prepped for his performance.

On the day of the sessions, Floyd was one of the few not on the bus. As he told Jeff Hannusch in I Hear You Knockin’, he took his own car up to Jackson; and it broke down along the way, making him so late that he almost missed his chance. Yet, when he finally stepped up to the mike, he got the first number down in just two takes, then nailed “Groove Me” on the first try. Only about a half hour had passed in the studio before he was back on the road for New Orleans to make a shift at work - quick, slick and meant to be.

All along, “Groove Me” was intended as the B-side of his single from the session. The preferred song,”What Our Love Needs”, also written by Floyd, had a more conventional beat and construction, with a smooth soul feel enhanced by Wardell’s evocative orchestration, adding strings and woodwinds to the mix. But, rather than treat “Groove Me” as a throwaway, Big Q channeled the song’s inner moxie, countering the quirky, off-balance rhythmic tensions of the verses with the quick propulsive releases of the choruses, so the music pulsed like some automated soul-funk hybrid under the singer’s assured, imperative delivery. Even though all involved considered it too groove-centric and idiosyncratic for mainstream soul radio, the song would soon prove them wrong.

After all the tracks had been cut, Malaco shopped each artist’s songs to Stax Records in Memphis, which passed on the entire lot, and then to Jerry Wexler at Atlantic, who did likewise. Thanks, but no thanks. As Bowman tells it, the setback took the wind out the the team’s sails, though they were still convinced they had cut some hits. Their first back-up came from a Jackson radio station program director who heard the material and thought Floyd’s songs had the most commercial potential. He encouraged Tommy Couch, co-owner of Malaco, to take a chance and release a single independently.

With no other viable alternative, the studio set up a new label, Chimneyville, and issued Floyd’s record (#435) in August of 1970. When George Vinnett, manager of WYLD, the premier soul station in New Orleans, received some copies soon thereafter, he fatefully gave one to his teenage niece who played it at a party with her friends. They all immediately flipped for the flip side and grooved on it all night long. That enthusiastic, unscientific focus group convinced Vinnett that “Groove Me” could be big, and he began pushing it on the air, much to Floyd’s initial consternation. The singer soon got over it, when the record took off all over town and began to break out regionally.

That’s when Atlantic swooped back into the picture to get a piece of the “Groove Me” action by providing national distribution for Chimneyville through their Cotillion subsidiary, which helped take the record to its #1 R&B, #6 Pop peak. That success, along with “Mr. Big Stuff”, the delayed-release hit for Jean Knight the next year, encouraged Wardell and his writers to pursue numerous other overtly rhythmic projects over the next few years.

Of course, King Floyd had his share of those cuts on subsequent 45s and two albums supervised by Big Q.

“Woman Don’t Go Astray” (King Floyd)

“Woman Don’t Go Astray” (King Floyd)

King Floyd, Chimneyville 443, 1972

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Another original by the singer, this song initially appeared on the his eponymous 1971 LP, released by Cotillion to further cash in on the success of not only “Groove Me”, but the #5 R&B, #29 Pop follow-up single, “Baby Let Me Kiss You”, a highly funkified variation on the theme of the prior hit. As for the prospects of “Woman Don’t Go Astray”, George Vinnett once again showed his prescience, lobbying to get the track released on a 45, convinced that it too could do great things. That came to pass in 1972, when the single version became another #5 R&B smash.

Another original by the singer, this song initially appeared on the his eponymous 1971 LP, released by Cotillion to further cash in on the success of not only “Groove Me”, but the #5 R&B, #29 Pop follow-up single, “Baby Let Me Kiss You”, a highly funkified variation on the theme of the prior hit. As for the prospects of “Woman Don’t Go Astray”, George Vinnett once again showed his prescience, lobbying to get the track released on a 45, convinced that it too could do great things. That came to pass in 1972, when the single version became another #5 R&B smash.

Simply constructed with just two alternating sections, the song’s appeal lies in the interplay of each different yet complimentary dance groove. The first is built around another hesitating, ostinato bass riff similar to “Groove Me”, while the other breaks into an upbeat swing feel that affords the tune forward momentum. Wardell’s arrangement avoided getting in the way, and focused on that interaction, staying in the stripped down mode of just drums, bass, guitar and organ, plus smatterings of horns throughout. Meanwhile, Floyd’s reliable tenor locked perfectly into the rhythmic mix.

“Woman Don’t Go Astray” appeared on Floyd’s fifth Chimneyville single and would be the last charting track of his career. Due to its success, the song was also included on his second LP, Think About It. Though he stayed with the label for a few more years and put out other good records, the singer and Wardell parted ways somewhere around 1973, due to the oft-used catchall of “creative differences”. Those in the know have said that Floyd was generally difficult to work with, to the point of becoming irrational at times; and things only got worse when when the hits stopped coming.

“It’s Not What You Say” (Michael Adams, Albert Savory, Wardell Quezergue)

“It’s Not What You Say” (Michael Adams, Albert Savory, Wardell Quezergue)

King Floyd, from Think About It, Atco 7023, 1973

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Here’s a great groover from the final days of the collaboration, which only appeared on Think About It, the last Floyd LP to have Big Q’s involvement. Again, Atlantic released it as part of its Chimneyville Series, but on the Atco imprint this time around.

It was a worthy collection that included a few cover tunes for the first time. The perennial “My Girl” was completely re-imagined and extended by Wardell and Floyd into an impressive, multi-part production with two monologues; and there were two Otis Redding-related numbers (nothing wrong with that!), including the title track, which also appeared on a single. With Floyd’s record sales down, Atlantic may have dictated the use of those songs to try (in vain) for wider appeal. Still, each got the distinctive Big Q treatment; and the bulk of the album’s material was sourced once again from his stable of tunesmiths, as well as Floyd and various co-writers.

Penned by Big Q with Michael Adams and Albert Savoy, “It’ s Not What You Say” is one of the most impressive loose-booty tracks Floyd and his producer made together and certainly should have had a spin-off single of its own. Using the same basic Malaco-era instrumentation from the Chimneyville rhythm section and horns, Wardell further textured the mix with some very effective added percussion, upping the funk quotient considerably. It’s another example of his ability to create intricately layered, interactively syncopated synergy among the players and vocalist, engendering a groove that strips away all excuses not to move.

Listening to this track again (and again), I am reminded why Floyd’s performances on funkier material generally seem his most satisfying. He had a pleasant enough voice, but a limited vocal range, which he compensated for by gearing his approach more toward the rhythmic energy in the music. It brings into focus the importance of having a collaborator such as Big Q, who intuitively understood how to bring out a singer’s strengths and minimize any limitations, and whose poly-rhythmic grooves dovetailed perfectly with Floyd’s emphasis on the meter of his delivery. No doubt such support was vital for the singer to attain the success he had in the business, even though he unfortunately did not fully appreciate the fact.

Call it miraculous, or call it destiny, as the singer did in describing to Jeff Hannusch the chain of events that led to his break-out years at Malaco. There’s no doubt in my mind that the King Floyd - Wardell Quezergue musical connection was a beneficent cosmic convergence for all concerned, including those of us still enjoying the results in the here and now.

Jean Knight's Biggest Stuff

Jean Knight, who came into this world as Jean Caliste, connected with Wardell in an equally unplanned and fortuitous manner. Her recording career began about five years earlier in her hometown of New Orleans, when she came to Cosimo’s studio to cut some demos for Henry R. ‘Reggie’ Hines. He and Lynn Williams co-owned Lynn’s Productions, a Mississippi-based talent management and production company which operated several labels up in the Delta. Hines had recently opened a branch operation with bandleader Al White in the Crescent City to find and develop talent. Among the young, local acts on his roster at that time were the Barons, and a female vocal group, the Queenettes (more about them later).

Jean Knight, who came into this world as Jean Caliste, connected with Wardell in an equally unplanned and fortuitous manner. Her recording career began about five years earlier in her hometown of New Orleans, when she came to Cosimo’s studio to cut some demos for Henry R. ‘Reggie’ Hines. He and Lynn Williams co-owned Lynn’s Productions, a Mississippi-based talent management and production company which operated several labels up in the Delta. Hines had recently opened a branch operation with bandleader Al White in the Crescent City to find and develop talent. Among the young, local acts on his roster at that time were the Barons, and a female vocal group, the Queenettes (more about them later).

Caliste’s first record resulted from that session, but actually came out thanks to another wheeler-dealer producer and label owner, Huey Meaux, a Texan with Louisiana Cajun roots, who was also at Cosimo’s recording a project on the great Barbara Lynn. When he happened to hear the demo tracks Caliste had done, he was impressed enough to contract to release the tunes, “Doggin’ Around” and “The Man That Left Me”, as a single (#706) on his Jetstream label in 1965. She adopted the stage name, Jean Knight, for the record; and it would stick. Subsequently, she cut two more singles in Texas for Meaux’s Tribe imprint; but he soon lost interest when none of her 45s did well. The recordings did allow the singer to get some club work around New Orleans and environs; but, by the end of the decade, Caliste was putting bread on the table by working as a baker, with musical prospects for Jean Knight looking pretty flat.

Then, as she related to Jeff Hannusch in The Soul Of New Orleans, out of the blue one day while downtown, she was recognized and approached by a stranger, Ralph Williams, who said he was a songwriter for Wardell Quezergue and had some material he would like her to record. Interested, she soon met with Big Q, and got a tape of songs to consider for an upcoming recording date at Malaco. Of those, she immediately was drawn to the concept of “Mr. Big Stuff”, but put off by the fact that it was paced as a ballad! So, she convinced Williams and head-writer Joe Broussard that it needed perking up to allow her to give the vocal some emphatic attitude that captured the spirit of the lyrics; and Wardell kept that in mind when he recorded the backing tracks.

As the story goes, and I’ve no reason to doubt it, he worked out the arrangements for all the songs to be cut at his first big Malaco instrumental tracking session, while in the car on the way from New Orleans to Jackson. No mean feat! What he came up with for “Mr. Big Stuff” was neither funk, New Orleans R&B, nor straight southern soul. Instead, he infused the tune with what might best be described as a hybrid Jamaican rock-steady feel. Whether it was intentional or coincidental remains open to conjecture; but it was still a fairly unusual slant for the US soul-pop mainstream at the time.

Taking the track at mid-tempo, Wardell had James Stroud keep the snare beat in the pocket on the two and four, allowing the kick drum just a touch of an off-beat, while the interacting patterns assigned to the guitar, bass and horns provided uplifting syncopations. The resulting innovative, infectious bounce afforded Knight evocative support for the take-charge attitude she brought to her vocal romp with the litany of put-downs penned by Broussard, Williams, and Carol Washington.

In contrast, the flip side ballad, “Why I Keep Living These Memories”, by Broussard and Michael Adams, provided a real change of pace and mood, showing Knight could be an effective songstress of the deep, as well. Most everyone involved with the sessions immediately thought “Mr. Big Stuff” had strong hit potential; but, as mentioned, circumstances would lead some to second guess that gut feeling.

Once both Stax and Atlantic had initially passed on everything cut at the school bus sessions, Malaco’s Tommy Couch began to question whether “Mr. Big Stuff”, which he considered a novelty number, was even worth trying to push. So, he left Knight’s tracks on the shelf to concentrate on getting the other material released, including setting up Chimneyville to issue the King Floyd single. It was not until early 1971 that Couch’s friend, Tim Whitsett, who worked at Stax and was a fan of “Mr. Big Stuff”, convinced still skeptical higher-ups at the label to reconsider and take a chance on it. The single came out around March, almost a full year after the recording date; and, by May, the song was #1 in the nation R&B, and had crossed over, climbing to #2 Pop. Later that summer, it became one of the biggest sellers Stax ever had, surpassing two million in sales.

Once both Stax and Atlantic had initially passed on everything cut at the school bus sessions, Malaco’s Tommy Couch began to question whether “Mr. Big Stuff”, which he considered a novelty number, was even worth trying to push. So, he left Knight’s tracks on the shelf to concentrate on getting the other material released, including setting up Chimneyville to issue the King Floyd single. It was not until early 1971 that Couch’s friend, Tim Whitsett, who worked at Stax and was a fan of “Mr. Big Stuff”, convinced still skeptical higher-ups at the label to reconsider and take a chance on it. The single came out around March, almost a full year after the recording date; and, by May, the song was #1 in the nation R&B, and had crossed over, climbing to #2 Pop. Later that summer, it became one of the biggest sellers Stax ever had, surpassing two million in sales.

Soon after her record went gold, Stax released the Mr. Big Stuff LP pictured above, produced by Big Q at Malaco with material by his staff writers. The album was decent enough, but contained nothing really outstanding beyond the hit. It didn’t even include her follow-up song soon to hit the charts, although the flip side made it in. Even so, the LP with that imposing blimp-daddy portrayed on its cover sold well; but, despite her flash of phenomenal success, Knight’s run at Stax would prove to be all too brief.

“You Think You’re Hot Stuff” (Broussard, Williams, Washington)

“You Think You’re Hot Stuff” (Broussard, Williams, Washington)

Jean Knight, Stax 0105, Sept. 1971

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

In age-old record business fashion, Big Q and company tried to keep Knight’s stuff from cooling off by making the next song to be pushed a relative knock-off of the first - not a replica that required a Part 2 designation, but certainly a close enough continuation of the sound and theme that it would be immediately recognized by anyone who had heard “Mr. Big Stuff” more than a few times. They had done similarly with Floyd’s second single.

Often, such ploys can range from lame to simply redundant, but, in this case, the writing of Broussard, Washington and Williams plus Wardell’s arrangement offered up music and a groove that still engaged despite that warmed-over feeling. Though this iteration still has the high-profile bounce, the rhythm track attack is harder-hitting; and Stroud’s drumming nicely slips and slides a bit more to the funky side. The result again gives Knight sturdy, dance-worthy support for the second bout of lyrical trouncing she delivers.

Released in the immediate slip-stream of her prior hit, “You Think You’re Hot Stuff” sold respectably, but reaction was far less intense. It barely got into the R&B top 20 by October of 1971 and went no higher, staying in the charts less than half as long as its predecessor. As for her remaining three singles that Stax released on into 1972, all failed to significantly chart or sell.

“Do Me” (Albert Savoy - Wardell Quezergue)Jean Knight, Stax 0150, November, 1972

“Do Me” (Albert Savoy - Wardell Quezergue)Jean Knight, Stax 0150, November, 1972

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

I first featured this tune, which comes from her final Stax single, back in 2006; and it’s certainly worth breaking out again here. I stand by my favorable assessment of the track in that post. Pop that thing! Yes, m’am.

Through no fault of her own, Knight remained an outsider at Stax. During her run, she was under contract with Wardell and company, who provided her with tunes cut exclusively at Malaco. The Memphis label felt her material did not mesh with its sound and direction. So, as she told Hannusch, they attempted to bring her into the fold by offering her good material from their in-house writers that she liked and deemed hit-worthy, but Big Q refused to let her record anything that didn’t come from his production team, no doubt in order to get the publishing royalties involved. So, it became a stand-off. Obviously, Stax wanted more control of Knight’s sound and a cut of the publishing action, too. When they could not get either, they simply refused to release anything else by the singer.

Wardell probably did not relent because he would have been a loser either way. He’d have no publishing income, if Knight did Stax material; and they might lure her away, as well. So he let the deal go under; and, since Malaco seemingly had nowhere else to go with Knight’s recordings, she was through with Big Q by late 1973. Music business power-plays do not go well for those without good options. It was a blow for Big Q’s operation, but much worse for Kinght, whose career never had a chance to fully develop. Stax, on the slide toward bankruptcy, never did sign her; and she bounced from label to label almost yearly throughout the rest of the 1970s, until having two more substantial hits in the 1980s working with producer Isaac Bolden in New Orleans. The last of those was a cover of Rockin’ Sidney’s strong-selling, go-figure novelty nonsense, “My Toot Toot”. In the 1990s, she put out two CDs and continues to perform at festivals and oldies shows up until the present day.

Bonnie & Sheila’s Limited Hang

Of the five acts who recorded sides as a part of these sessions, Bonnie & Sheila are certainly the most obscure. Not only is their record hard to come by these days; but it was elusive at the time of its release. Bonnie told Rob Bowman that she was not sure it was even issued, since she had never seen a copy! Well, Bonnie, if you are still unsure, it was released. I had seen several promo copies, before I chanced upon and bought this stock copy from a UK seller. For those who might be looking for one, note that Sheila’s name is misspelled on the label, making the 45 a bit tricky to search for online.

“You Keep Me Hanging On” (Bonnie Perkins)Bonnie & Shelia [sic], King 6352, 1971

“You Keep Me Hanging On” (Bonnie Perkins)Bonnie & Shelia [sic], King 6352, 1971

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

“I Miss You” (Bonnie Perkins)

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Credited as songwriter on both sides of this King single, Bonnie Perkins also had her full name disclosed in Bowman’s box set notes along with that of her singing partner, Sheila Howard. As he also indicated, this was the only commercial release the duo had.

With these tidbits of information, I was able to do further research leading me to believe that Bonnie had also done some recording in the mid-1960s which resulted in two prior releases. On one of them, she worked with not quite ready for prime-time operator ‘Reggie’ Hines, a connection she had in common with the Barons and Jean Knight (see the above section and/or the prior post for details). Bonnie appears to have been a member of the Queenettes, a female vocal group who like the Barons, were signed by Hines to Lynn’s Productions at the time. Both cut several songs for the 1966 Folkways LP, Roots: Rhythm and Blues, a compilation featuring artists from Lynn’s roster, produced by Hines and Al White at Cosimo’s in New Orleans. I discovered Bonnie’s involvement when I checked her other songwriting credits in the BMI database, and found her listed as co-writer on two of the Queenettes’ three tunes on that album. Also credited on those were Hines, probably just getting his producer’s cut; and three other names: Bernadette Moore, Sylvia Moore, and Veronica Thompson, who I am assuming were other members of the group.

If you are an avid collector and/or have been paying close attention here for the last few years, you might recall that Eddie Bo also recorded a group shown as the Queenetts on one of the few 45s for his under-funded and very short-lived Fun label. If that was the same group, which I think is likely, the resulting, extremely rare single (#304) was probably their first release. Both sides were Bo compositions, “So Lucky In Love” b/w “How Long (Can I Hold MY Tears)”; and, from the performances on clips I’ve heard, there were probably fewer than a four members at that point. The participation of Bonnie or the still mysterious Sheila on those two tracks remains unclear.

But back to the 45 at hand. Both of these unassuming pop sides sound like throwbacks to that earlier era, and rather out of place in comparison to the other material recorded along with theirs. I’m not really sure what Big Q expected to achieve commercially going with Bonnie's songs, or why he would not have asked his writing team to cook up something more current for them to release as a debut.

The tunes obviously benefited greatly from Wardell’s arrangements, especially the top side, “You Keep Me Hanging On”, which he presented in the best possible light as a hooky dancer with a great groove courtesy of the in-house band (later known as the Chimneyville Express) at his disposal. I’ve seen this track described as New Orleans funk in several places; but that’s not really what’s going on here, even though Stroud's drumming, syncopated by Big Q design with tambourine reinforcement, is the saving grace of the track. Rhythmically, it’s another hybrid, with all parts, including the vocals, set up with the producer’s usual emphasis on emphatic rhythmic interaction, and performed with such tight tolerances that, once the initial boom-da-boom beat of the intro locks you in, your attention doesn’t fade until the music does. I particularly like the way he reinforced the chorus by repetition, wrapping the chord progression back around itself to make it build. All in all, the track is no doubt a great pop production, creating something engaging out of modest material at best. But I still think the sound was just about five years too late out of the gate to catch a break in 1971, especially on the funk-heavy King label, which seems not to have paid it much mind at all.

I am assuming that Bonnie was the stronger and more expressive of the voices on these cuts, but I have found no clear back-up for that. It’s easy to speculate on what might have happened had that singer worked solo for Wardell on some more challenging material. For a prime example of what she was capable of, seek out “You’re Not The One For Me”, an unissued Malaco track, ostensibly by the duo but with just one main vocal, that was written by Tommy Ridgley and first came to light on the grapevine compilation, Wardell Quezergue Strung Out: The Malaco Sessions. It’s a soulful stunner of a performance on a nicely constructed soul ballad with a very lush, high-class arrangement by the Master, just miles (and miles) beyond what the King sides had to offer. Why it was not released at the time remains another Bonnie & Sheila question mark.

Instead, as things stood, neither of the singers hung on after their first record received its stealth release, and “You Keep Me Hanging On” quickly became their head-bobbing swan song.

Rediscovering the Soul of Joe Wilson

There were supposed to be two deep soul specialists on the school bus to Malaco in May of 1970; but, as noted earlier, C. P. Love gave up his spot at the sessions so that King Floyd could have a shot with ”Groove Me”. That left Joe Wilson, a very capable vocalist with an expressive style and extremely supple range, who was arguably the best pure singing talent signed by Big Q and Elijah Walker. He could easily ascend into high tenor and falsetto, sounding somewhat similar to the great Ted Taylor when he did.

Despite his gifts, Wilson never gained wide recognition when he was making records, although he has belatedly received his share of well-deserved accolades from collectors and fans who appreciate vintage tracks from the deeper end of the soul spectrum. Several of his earliest sides, cut in the mid-1960s for Cosimo Matassa’s White Cliffs label, are prized for the artistry and emotive intensity of his delivery. In addition, his choice work at Malaco has also become more sought after these days, and somewhat easier to come by.

I don’t own any of Wilson's three fairly rare White Cliffs singles, nor do any of the tracks appear to have been released on comps [A general, well-annotated White Cliffs retrospective is way past due]; but it would surprise me if Big Q were not involved in at least a couple of the productions. As for the singer’s Malaco material, I’ll be covering most of the released sides here; but for a comprehensive overview, Gary Cape’s Soulscape label has compiled virtually every track Wilson did with Wardell at Malaco, including six that were unissued, as part of the 2009 CD, Malaco Soul Brothers Volume 1.

Online, Sir Shambling’s Deep Soul Heaven, researched and compiled by John Ridley, one of the true experts in the field, is the go-to site for the basic lowdown on Wilson’s career (and so many others!), including a discography and some tracks to hear. So, for more details, open up a window on that, too.

“Sweetness” (J. Broussard-A.Savoy-J. Wislon)Joe Wilson, Dynamo 147, 1971

“Sweetness” (J. Broussard-A.Savoy-J. Wislon)Joe Wilson, Dynamo 147, 1971

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

This fine 45 is the result of Joe Wilson’s initial session at Malaco. The impressively sung, deep soul B-side. “When A Man Cries”, written by Joe Broussard, is available at Sir Shambling’s page on Wilson, or can be streamed courtesy of 9thWardJukebox on Youtube. Due to the number of tracks I’m covering, I’m passing this ballad up.

As previously detailed, when Atlantic and Stax expressed no interest in any material by Wardell’s school bus (and one broken down car) artists, Tommy Couch was left with the dilemma of how to get the tracks placed, and came up with various solutions over the next year. For Wilson's record, he presented the tracks to Musicor, a New York City company which made arrangements for a national release on their R&B subsidiary, Dynamo Records. The record came out in the Spring of 1971; with Wardell getting full credit on it as producer and arranger.

An upbeat spash of fairly straight-ahead southern soul written by Broussard, Wilson and Albert Savoy, “Sweetness” has a great, groove suitable for dancing, a somewhat unusual song structure, and a well-executed arrangement with horns and strings. Following the short, catchy instrumental intro, which repeats again mid-song, the body of the song is front-loaded with the bright chorus, which predominates. The verses, such as they are, alternate with it thereafter, marked by a shift into minor chords. Overall, the tune was well-suited to Wilson’s vocal style; and he sang it with surprising conviction, considering that it was pretty lightweight fare; but that’s the way he rolled.

Although Ed Ochs’ Soul Sauce column in Billboard gave “Sweetness” a pick in April of that year, along with dozens of other releases, the song didn’t make much impact on the airwaves. Musicor experienced some business setbacks around that time and had just gone through an ownership shuffle. Unbeknownst to Tommy Couch, the company was about ready to shut down or sell off Dynamo, which would return under new management a few years hence as a disco label. So, the deck was stacked against the record; and any push they gave it was probably perfunctory at best. Interestingly, this single was re-issued on Musicor (#1501) in 1974; but it again made no waves.

Meanwhile, Wardell had recorded more songs with Wilson, including “Let A Broken Heart Come In” and “(Don’t Let Them) Blow Your Mind”, which Couch and company released on their in-house Malaco label (#1010), likely in early 1971, as well. But, with no distribution or money to promote it, the record wasn’t going anywhere, so Couch again went to Musicor for a re-issue. For the resulting single, either he or Dynamo substituted another Wilson track, “Your Love Is Sweet (To The Very Last Drop)”, for the top side, and put “Let A Broken Heart Come In” on the flip. It dropped not long after #147 fizzled.

“Your Love Is Sweet (To The Very Last Drop)" (A.Savory-M.Adams-J. Wilson)Joe Wilson, Dynamo 149, 1971

“Your Love Is Sweet (To The Very Last Drop)" (A.Savory-M.Adams-J. Wilson)Joe Wilson, Dynamo 149, 1971

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

With the resounding success of King Floyd’s “Groove Me”, Big Q and his crew were emboldened to give a similar treatment to many sides on the Malaco production line. Rather than seeing the hit record as a fortuitous fluke, they turned its quirky, herky-jerky groove concept into a template to fashion other potential hits for not just Wilson, but a number of artists they would bring to Malaco over the next few years. It’s an oft told music business truism that nobody really knows which song will become a hit, or how it happens. So, as in gambling, people try all sorts of angles looking for a sure thing, facing the unknowns of chance with ritual, superstition, various questionable formulas for winning and dogma about what works. Obviously, just copying what you did before, or what somebody else did, to get the desired result has always been a popular gambit. Never forget the Skinner box.

Thus, we have “Your Love Is Sweet”, one of Wardell’s musical, mostly one-trick wind-up toys. But, as always, it’s a fun trick, and extremely well-done. Getting caught up in the syncopated inner-workings of all the parts provides a few minutes diversion. But, like the the various sweets mentioned in the lyrics, the result is mostly empty calories, soon forgotten as we’re off in search of our next sugar high. The song's kinship to Floyd's hit is likley what attracted Dynamo to it; and it just as easily could have shown up as a filler cut on one of Floyd’s albums. Wilson did a good enough job getting down and becoming one with the groove; but the tune was really not well-suited to favor his vocal gifts.

“Let A Broken Heart Come In” (Quezergue-Savoy)

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Here we find Big Q back working in the upbeat southern soul-pop mode, a better match for Wilson’s smooth moves. It’s an arrangement that had Stroud lay down straight in the pocket snare beats with some customary syncopation mainly in his bass drum footwork, providing deft support both for the ascending/descending progression of the verses and harder drive of the other segments.

Here we find Big Q back working in the upbeat southern soul-pop mode, a better match for Wilson’s smooth moves. It’s an arrangement that had Stroud lay down straight in the pocket snare beats with some customary syncopation mainly in his bass drum footwork, providing deft support both for the ascending/descending progression of the verses and harder drive of the other segments.

Though not a truly great song, it’s certainly good enough that I think it should have remained the single’s A-side, as on Malaco 1010; but, knowing with hindsight the status of Dynamo at that point, such choices ultimately made no difference. The 45 was marked for oblivion. Musicor jettisoned the label soon after this release, giving it the distinction of being the last one of the series.

Wilson’s next and final record through Malaco came about probably late in 1972, when two more tracks produced by Wardell, “You Need Me” and ”The Other Side of Your Mind”, came out on the limited-edition label, Big Q (#1002 - see the label shot of this rare bird at Sir Shambling’s), probably just to get it to some DJs in the New Orleans area and build a buzz for “You Need Me”. Soon thereafter, the single was picked up and re-issued nationally by Avco, another New York-based company, which had recently released two 45s on Dorothy Moore, one of Malaco’s own artists.

“You Need Me” (A. Savoy-W. Quezergue-J. Wilson)

Joe Wilson, Avco 4609, 1973

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

As you may have noticed by now, I don’t usually concentrate on ballads here at HOTG; but this track has that rare combination of a slow pace and a good groove. Not to mention that it is a classic Quezergue production and Wilson performance, superbly rendered with a well-recorded, full orchestral treatment, the beauty of which is somewhat impaired by the sonic limitations of what the 45 medium (let alone a flimsy mp3 file) can deliver. But you know it’s all good when the fade seems to come far sooner than its 3:32 running time, and you’re not ready for it to end. If you feel this track, I recommend getting the Soulscape CD, which has an extended version in far higher fidelity. It was a big selling point for me, and I’m not generally a fan of down-tempo sides.

In essence, “You Need Me” no has gimmicks. The lyrics are as simple and straightforward as the structure itself. Musically, it’s all about the many entrancing nuances of the interwoven parts, all built upon the subtly syncopated patterns Wardell had Stroud put down. Wilson took the track entirely in the higher range of his impressively emotive tenor, but never oversang, allowing him the latitude to impart feelings of vulnerability and tenderness that only a first class soul man in total control could deliver.

Without a doubt, this is the song that woke me up to the fact that Joe Wilson is the real deal. Too bad it didn’t affect more people that way back in 1973. As it makes abundantly clear, Wardell’s greatest gift was his ability to artfully provide a production platform for a singer to be at his or her best. He didn’t always reach the near perfection of this production, but he was constantly striving for that goal, and got things right far more often than not.

“The Other Side of Your Mind” (A. Savoy-W. Quezergue)

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

How does one follow an impeccable performance? Few flip sides would stand a chance against “You Need Me”. But we have to take each song on its own terms and decide if the execution matches the intent; and, in this case, I think something a little bit funky and off the wall was a good way to go.

How does one follow an impeccable performance? Few flip sides would stand a chance against “You Need Me”. But we have to take each song on its own terms and decide if the execution matches the intent; and, in this case, I think something a little bit funky and off the wall was a good way to go.

In this case, it seems Big Q was gong for a Staple Singers at Muscle Shoals feel, which is what the Chimneyville Express rhythm and horn sections delivered. It’s a mid-tempo southern soul arrangement with a country-ish sway to the bass, juxtaposed with subtle syncopation in the kick drum and hi-hat push-pulls, tasty guitar licks, Memphis Horns-type fills, plus Wardell’s lower mid-range tonal coloring on electric piano. Nothing wrong with copping a popular sound of the day, when you can pull it off so well. The lyrics are kind of unfocused and offbeat; but Wilson worked with them, applied some grit, and got the job done, although the funky side was not his true forte.

Without a doubt, the Big Q/Avco single was the highpoint of Joe Wilson’s recording career, which lasted a little over two decades, though with some gaps. After “You Need Me” failed to get him the recognition he deserved, he apparently had nothing else released until the 1980s came around, when he again worked with Wardell on several projects. As shown on Sir Shambling’s discography, there was as a one-off single on the BFW label in 1980, and a reprise of “You Need Me” for Maria Tynes’ Ria label in 1987, appearing on a single [which we’ll get to at a later date] and the LP, Come Inside.

For the next installment, I’ll be doing one more Malaco-related post, covering a spate of mainly one-shot singles Wardell produced there for a variety of artists. Hope it won’t be too long. . . .