Tracing Benny Spellman's Fortunes, Pt. 2

Picking up more or less where my prior post left off, I’ll start with another of the late Benny Spellman’s unreleased, Allen Toussaint-produced tracks, probably recorded prior to 1963 from the sound of it. I forgot to include this one this last time, and want to get it in, since it’s a great little number, and one of my favorites. The song first appeared on the 1984 Bandy LP compilation, Benny Spellman (a/k/a Calling All Cars), then on the Fortune Teller collection, which first Charly then Collectables put out later in the 1980s.

“You Don’t Love Me No More” (Allen Toussaint)

Benny Spellman, Bandy LP 70018, 1984

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

I can’t understand why Minit didn’t run with this one at some point, as it’s the perfect vehicle for Benny’s buttery baritone and sounds closer to what Toussaint was writing for labelmate Irma Thomas at the time - the soulful side of pop. Had he given Benny more material like this and actually released some of it, the singer might have had more shots at significant airplay and record sales, instead of remaining a one minor hit wonder.

Toussaint’s impending departure for the service, and Minit’s fate to be sold off by Banashak to outside interests for some needed quick cash insured that Benny’s remaining time with the label was anticlimactic at best; and, when the operation moved to the West Coast, the new Minit abandoned its New Orleans artists. But, as luck would have it, a new label in town was just getting off the ground and afforded Benny a couple of more spins on the recording wheel of fortune.

“Walk On Don’t Cry” (M. Rebennack - P. Harris)

Benny Spellman, Watch 6332, 1964

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Watch Record Company was established in 1963 by Henry Hildebrand, Jr., owner of All-South Record Distributors, and Joe Assunto, who ran the One Stop Record Shop on South Rampart Street in bustling downtown New Orleans. From the outset, what made the label so promising was the creative involvement of talented arranger Wardell Quezergue and musical multi-tasker Earl King. They co-produced most of the sessions and wrote many of the songs, having first collaborated two years earlier on King’s own memorable records for Imperial. The two had also been in the contingent of singers and musicians that Joe Jones took to Detroit early in 1963 to audition for Motown Records, as the New Orleans scene was at low ebb. Remarkably, King ended up being the only one that Berry Gordy put under contract (probably for his songwriting skills, as he never had a Motown release), which is why he was obliged to stay behind the scenes at Watch and did not put out any records of his own for five years.

According to Jeff Hannsuch’s notes to the 2000 Mardi Gras CD compilation, New Orleans Soul ‘60’s Watch Records, Benny’s session for this 45 was the first one Quezergue and King supervised for Watch; but the record’s release took a back seat to Johnny Adams, who had the label’s initial single (#6330), followed by Dell Stewart, a King protege, who scored a strong local hit with “Mr. Credit Man”. Benny’s record was next out of the gate; and, as can be heard, the Watch team stayed with Toussaint’s concept and had the singer continue in the pop mode. On the mid-tempo top side, “Walk On Don’t Cry”, a nicely turned out tune written by Mac Rebennack and the unknown (at least to me) Pierce Harris, the only slight give-away that this might be a New Orleans record was the subtle syncopation on some of the drum rolls, especially in the ride-out. Otherwise, it might just as well have come out of Chicago, Detroit, or New York. Benny’s melodic, assured delivery could have made it a sure thing, but the side was passed over in favor of the flip.

“Please Mr. Genie” (Earl K. Johnson - Benny Spellman)

“Please Mr. Genie” (Earl K. Johnson - Benny Spellman)Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

An enjoyable, highly danceable novelty number, “Please Mr. Genie” one-upped “Fortune Teller” for fanciful subject matter, and got the attention of DJs and record buyers around town. King co-wrote it in his own classic, quirky style, tailoring it specifically for Benny. Quezergue’s arrangement emphasized the hooky, vaguely oriental sounding guitar licks, surely played by Earl himself, and insured a more overtly syncopated, hometown kind of groove, by using funk pioneer Smokey Johnson. Rounding out the track was Quezegue’s signature big horn section, adding some needed heft to the rather lightweight fun. Although the song didn’t demand as much vocal technique as the top side, Benny found just the right tone to sell it, dropping down into his signature bass register at the fade out for good measure.

Despite the favorable local response, the song did not break out anywhere else in the country. Watch had no national distribution to speak of; and All-South lacked the resources and staff to promote in distant markets. Hildebrand and Assunto rarely sought to even lease their singles to larger labels, virtually eliminating any chances of wider recognition for their records and artists.

Benny’s follow-up, “Someday They’ll Understand” b/w “Slow Down Baby (Don’t Drive Too Fast)” (#6336), proved to have less impact, hamstrung by weaker material that lacked Earl King’s reliable touch. The A-side’s plodding pop was improved on by the bluesy soul on the back, obviously going for a Ray Charles type feel that Benny handled well, really digging in for an impressively powerful finish; but neither side played to his strengths. The single wound up being his last for Watch.

Also in 1964, probably inspired the local success of “Please Mr. Genie”, Joe Banashak issued a quickie single on Alon (#9018) featuring Benny doing “T’ain’t It The Truth”, which he had either recorded prior to 1963 or overdubbed his vocal onto later. It was a slightly rearranged version of a Toussaint tune recorded four years earlier by Ernie K-Doe and released on Minit before “Mother-In-Law” broke big.

Also in 1964, probably inspired the local success of “Please Mr. Genie”, Joe Banashak issued a quickie single on Alon (#9018) featuring Benny doing “T’ain’t It The Truth”, which he had either recorded prior to 1963 or overdubbed his vocal onto later. It was a slightly rearranged version of a Toussaint tune recorded four years earlier by Ernie K-Doe and released on Minit before “Mother-In-Law” broke big.Benny did a commendable job with the re-make; and I think I actually prefer his take to K-Doe’s (something Benny might well appreciate were he still with us); but I doubt the single got much action. It was such a rushed job that Banashak slapped a loose, inconsequential studio jam instrumental on the B-side, “No Don’t Stop”, onto which he had overdubbed Benny, sounding plainly uninspired, and some female vocalists singing the title phrase over and over. Regardless, the release of “T’ain’t It The Truth” and his leaving Watch opened the door to the possibility of Benny working with Toussaint again; and though their reunion in the studio did happen a bit later, circumstances would not favor a fortuitous outcome.

Financial setbacks coupled with Toussaint’s getting drafted had caused Banashak to briefly consider getting out of the record business; but he soon had a change of luck and mind. Chris Kenner’s “Land Of 1000 Dances”, which had not done much when it first came out on Instant in 1962; began getting played around the country the following year, perking up sales considerably. That bump caused Atlantic Records to come to Banashak proposing to put out an LP on Kenner and capitalize on the song’s popularity. Not only did they lease “Land Of 1000 Dances” but also a lot of other back catalog Kenner material for the album. With that infusion of cash, Banashak managed to keep his labels going from 1963 to 1965. He used some other producers for new Instant sessions and also released tracks on Alon by various artists that Toussaint had socked away before leaving for military service, which probably was the source of Benny’s first single for the label. Later, Toussaint also began providing Alon with a supply of mainly instrumental tunes cut in Houston with the Stokes, the band he put together at his Texas base.

In 1965, Toussaint returned to New Orleans and a less vibrant recording scene, making his professional prospects less rosy than they had been. Due to the sale of Minit, most of the artists he had worked with before had scattered to the wind; and business at Banashak’s remaining labels wasn't promising. Kenner’s 45 had been the only significant seller in the prior two years, and it reached just the lower end of the top 100. Thus, even as Toussaint went back to work for the label owner, producing projects mainly for Alon, he felt he needed a fresh start and began seeking an exit strategy.

Probably unaware of all that uncertainly just beneath the surface at Alon, Benny jumped into recording with Toussaint again, hoping the once and future hit-maker might help him find a way back into the charts. New sessions resulted in Benny cutting enough Toussaint-penned material to fill up three more Alon singles. But, by the time the first of those, “The Word Game” b/w “I Feel Good” (#9024) came out in 1965, Toussaint had left the fold for good to form a new production company with Marshall Sehorn and steer the career of Lee Dorsey.

Facing yet another unexpected setback, Banashak must have been somewhat encouraged when he got Atlantic to take over the “Word Game” single as well as a strange little two-parter called “Timber” credited to one 'Candy' Phillips, which actually was a Chris Kenner record written and produced by Eddie Bo, soon to be Toussaint’s successor in the musical chairs of the record business.

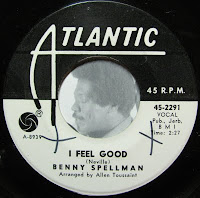

“The Word Game” (Neville)

Benny Spellman, Atlantic 2291, 1965

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Taking another stab at making Benny a novelty artist, Toussaint reworked an instrumental track he had done in Texas with the Stokes, which would later appear in its original form as “Young Man Old Man” on Alon 9029. To that he added Benny singing/talking some pre-school level lyrics which transformed the tune into “The Word Game” (...when I say a word, you say the opposite...). It appears to have been inspired by and specifically designed to ride in the slip-stream of Shirley Ellis’ silly (but fairly funky) big-seller, “The Name Game”, which hit the charts in early 1965 and got up into the Top 5. Attempting to siphon some sales off of an existing hit was an often tried music business ploy; and Toussaint was not above it from time to time - Banashak may even have suggested it in this case, as money was tight.

Whatever you think of the motivation for this production, there’s nothing really wrong with the underlying track, which has a “Hand Jive” kind of syncopated bounce with some great added tambourine action, or with Benny’s performance, which seems genuinely good-natured. The game Toussaint concocted was even much less complicated than the tangled rules of “The Name Game”.

It has been reported that “The Word Game” did alright around New Orleans; and maybe it could possibly have sparked a flash of oppositional game-song fever across the land, except for a major monkey wrench. While Atlantic agreed to release this single, it doesn’t seem they did much more than test-market it as a promo (as seen in the pictured copy - you rarely run across a stock copy), and took no pains to promote it - that is, pay anybody elsewhere to play it. That’s too bad, not because “The Word Game” really deserved to be a hit, but because it kept DJs from paying enough attention to flip the record over and discover the side that should have gotten the attention.

“I Feel Good” (Neville)

“I Feel Good” (Neville)Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

This exuberant, invigorating piece of pop writing and production, firmly planted on the rockin’ side of R&B, definitely lives up to its title, enough so to be downright addictive. During this period, Toussaint did some experimenting with rock elements in his writing and arranging, another example being the Billy (Al) Fayard single on Alon "I Get Mad, So Mad" with its Beatles/British Invasion influence.

“I Feel Good” (remember the Beatles’ “I Feel Fine”?) demanded little in the way of range or melody, just plenty of good energy and feeling, which Benny certainly delivered, as did backing singers Toussaint and Willie Harper, who were essential to amping up the intensity of the chorus, augmented by Toussaint’s sanctified piano running. If a calculated risk had been taken to make “I Feel Good” the plug side, and had Atlantic seen fit to push it, the song might have crossed over and found an audience; but, expectations were way too low.

[Note: My near mint promo copy of this single is a bad pressing and has a lot of distortion in the grooves, so I sourced the audio for both sides from the Fortune Teller LP. I still haven’t found a decent, affordable replacement for the 45. If all the Atantic promos sounded this crappy, there's another good reason for radio's lack of interest, right there! ]

Banashak released Benny’s other two Alon singles in 1966 after Toussaint was long gone. They stayed local and likely had very limited runs, judging from the prices they sell for these days. I can’t vouch for the quality of the material or performances on “It Must Be Love” / “Spirit of Loneliness” (#9027) since I’ve never even seen a copy, let alone heard the songs; but both are listed in Toussaint’s BMI catalog; and I’m pretty sure neither has ever been re-issued..

On the other hand, Benny’s final release for the label, “It’s For You” b/w “This Is For You My Love” (#9031), can be a bit more easily accessed; as the A-side was a part of the Fortune Teller LP/CD collection, and the other side showed up on the limited edition 1984 Bandy LP discussed earlier. Both are worth hearing, even though not Toussaint’s best work, revisiting as they do familiar pop territory, including the musical changes of “Fortune Teller” on the B-side.

With one classic record (“Lipstick Traces”/“Fortune Teller”) for Minit and a long string of commercial underachievers to show for his years of collaboration with Benny, one might think Toussaint would have cut the singer loose once free of the house of Banashak. Yet, late in 1966, he and Sehorn gave Benny the opportunity to record a single for their new Sansu label.

“Sinner Girl” (Alen Toussaint)

Benny Spellman, Sansu 462, 1967

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

Beginning in 1965, Lee Dorsey’s string of hit records, released on the New York-based Amy label, provided the bread and butter that kept Toussaint and Sehorn’s partnership, Tou-Sea Productions (later re-branded as Sansu Enterprises), solvent even as much of the rest of the New Orleans record business collapsed in a smoldering heap around them.

Due to that success, it’s not surprising that Toussaint sometimes modeled his writing for other artists after his work with Dorsey, hoping for some resonance with listeners and record buyers. Such was the case with “Sinner Girl”, the plug side of this single, which could have just as easily turned up as a B-side or LP cut for Dorsey, owing to the similarity of its changes, arrangement and funky, mid-tempo groove to “Get Out My Life Woman”, which had done quite well for Dorsey early in 1966.

“If You Love Her” (Allen Toussaint)

“If You Love Her” (Allen Toussaint)Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

For the flip side, Toussaint gave Benny something more adventurous to work with, a hook-laden, melodic, semi-precious pop gem with some nice structural complexity and an irresistible rhythmic flow. “If You Love Her” could have been strong enough to contend for A-side status had it not been left somewhat incomplete - missing not only lyrics on the first part of the third verse but also an instrumental solo on the break before the final chorus and fade. Indeed, it was unusual for Toussaint to neglect putting the finishing touches on a tune prior to its release, but the omissions do not detract much from enjoying the tune, if noticed at all. It seems a shame though to have it happen on a song that otherwise meshed so well with Benny’s vocal abilities.

That the record was Benny’s only Sansu appearance and did not make much of a stir commercially likely had nothing to do with his performance or the material. None of the many worthy singles by the label’s artists fared particularly well in the US marketplace - save for Betty Harris’ lone hit, “Nearer To You”, which got into the Top 20 in 1967. Granted there was a lot of competition from domestic soul and pop acts as well as the overflow of British bands on the airwaves; but Sansu’s national distributor, Bell, deserves some of the blame for either being unwilling or unable to give the label’s releases the strong promotion they deserved and needed to break out. The eventual shut down of Sansu in 1968 or 1969 was directly due to that inability to generate hits and the necessary sales that went with them. In addition, the music business was beginning a change of orientation from singles to albums. Sehorn and Toussaint would go on to follow the trend to success; but Benny and nearly all of his Sansu peers would not be with them.

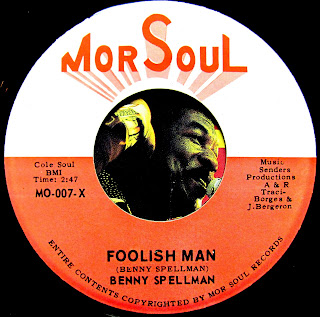

It must have been at about this point, if not before, that Benny realized his career in entertainment was no longer sustainable. Changes in popular tastes hit the New Orleans R&B scene hard, seriously limiting recording and on-stage opportunities. Around 1968, he had his last 45 release, two original songs on the micro-label, MorSoul.

“Foolish Man” (Benny Spellman)

Benny Spellman, MorSoul 007, 1968

Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

I’m including both sides of this single not just because it was Benny’s final one. I think his choice of direction on them is revealing, as well. A fine, effective soul-pop ballad, “Foolish Man” offers certainly one of his best recorded performances. The changes have a subtle sophistication, maybe even a bit jazz-influenced, and perfectly support the expressive lyrics. Kudos to the young A&R man, Traci Borges, for setting up a sympathetic arrangement that simply allowed Benny to shine. Without doubt, it was right in his sweet spot.

“Dont’ Give Up Love” (Benny Spellman)

“Dont’ Give Up Love” (Benny Spellman)Hear it on HOTG Internet Radio

In the “And Now For Something Completely Different” category, we are confronted with the polar opposite side, “Don’t Give Up Love”, in which any semblance of subtlety and sophistication have been tossed out in favor of attaining an undeniable groove and party atmosphere. The changes and arrangement are minimal, the execution direct and raw; but this sucker grabs you and demands that you move, sounding like some unpolished Stax outtake meant for Rufus Thomas with the young Bar-Kays throwing down in the studio.

Judging just the song or vocal, they seem to barely merit even the B-side; but Benny, Borges and band really bring a spirit to bear, heavy on the hard driving soul - no making things pretty and palatable for the pop mainstream. Even with the fake crowd chatter in the background, Benny’s ability to summon such a convincingly spontaneous and joyous dance groove speaks to his resources as an entertainer that rarely made it onto his recordings - more’s the pity. I’m certainly glad he got one last chance to let that genie out of the bottle.

Somewhere during this same period, Benny also cut a very basic demo of a deep soul ballad called “Let’s Start All Over”, probably an original, for Eddie Bo, who was doing A&R at Scram; but nothing came of it. The performance first appeared on the Tuff City/Night Train various artist CD compilation, The Best of Scram Records. There’s another track on the edition of the CD I have (1997) that is also credited to Benny, “For Once In My Life”, which was actually sung by the Jades; but that error seems to have been corrected on the later version of the album available for download. Since Benny never had a release on Scram or the related Power (Power-Pac) label, I find it ironic that the CD cover is a photo of him superimposed in front of a Scram label logo. Even calling the collection a Scram “best of” is a stretch, as few of the other songs on the CD were on Scram, either - several appeared on Power(Pac), and most were never released at the time. So, buyer beware.

Although Benny took a day job representing a beer company to make ends meet, he continued to perform from time to time and was a popular regular at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival for many years. Looking back at his decade of sporadic recording, it can’t be honestly judged a success for a variety of reasons I’ve cataloged in this series of posts; but he did make some good records and turned in a number of noteworthy performances. Though he seems never to have been a high priority artist, at least he got to work with one of the city’s premier writer/producers for most of the run.

In the end, despite whatever else he recorded, Benny will always be remembered for those two timelessly cool tracks he made with Toussaint, “Lipstick Traces” and “Fortune Teller”. The many fallen-by-the-wayside artists we discuss here at HOTG should all have been so fortunate.